Procedure & scientific background of our school-based prevention

Our tobacco prevention program in local schools is run entirely by volunteer medical students within our network, who are specially trained for these visits. The students who visit your school will depend on which medical colleges are in the vicinity. Click here to view a list of the medical colleges in our network. Our school visits usually include a scientific survey, as well as student/teacher involvement and information letters for parents; you can read more about our research here. To enable a better overiew, the program presented in schools should consist of the following two segments:

- An interactive assembly with age-based intervention (45 min.)

- An interactive station setup in the classroom (80 min.)

Assembly: Mirroring, athletic performance, mood, advertising (45 min)

The first 45-minute segment, which is supervised by at least two medical students and teachers, takes place with all the 7th graders together in an assembly hall in order to reproduce the group effects, which we were able to measure in a pilot study, and to include the extended student peer group [1].

During the first 20 minutes of the assembly, we conduct our “mirroring intervention”: Students take a selfie using the Smokerface App on their smartphone or tablet. Using an offline router solution, these 3D selfies are then transferred onto a projector and displayed side by side. Random mode is then activated and the next tablet(s) is hooked up. While their tablet is hooked up to the projector, a student can make changes to their own selfie, which is 3D-animated and touch-responsive. The effects of this intervention on the predictors of smoking, according to the theory of planned behavior, were measured by us in a pilot study and were also published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research [1].

During the last 25 minutes, an interactive PowerPoint is presented, which contains video elements, among other things, that are not suited for the classroom: A short clip from the 2014 World Cup Final is analyzed (students comment on a sprint by Manuel Neuer against an opposing striker), starting with Neuer’s initial degree of performance in order to then discuss the soccer player’s increase in physical performance that results from not smoking. Age-appropriate topics, such as saving money, the effects of addiction, and stress vs. relaxation are addressed. Finally, an advertising analysis is conducted (If you wanted to sell cigarettes to your classmates, how would you advertise them?), which includes real-life examples to strengthen social skills (local photography at school bus stops, which students encounter in their everyday lives) [2].

Classroom: Interactive Station Setup (80 min.)

Four interactive stations are set up in the classroom. The class is divided into three groups (students may choose their groups) that will rotate between the four stations (switching every 20 minutes). Three trained medical students split up into the three groups and participate in the discussion; there should be an average of 6-7 students per small group.

The goal of these stations is to provide the students with an understanding of the fundamental harmful mechanisms of smoking that effect the body, as well as to provide age-relevant and relatable examples to strengthen their self-responsibility and self-awareness, and to start a discussion. The station setup, the hands-on approach, and the youth-friendly nature of the presentation are aimed at creating a positive image of a smoke-free lifestyle for the students. In addition, the playful approach aids in communicating preventative knowledge related to smoking with the use of practical exercises and activites, which emphasize aspects that are relevant to the students’ lives. All experiments are set up and conducted by the students. The specially-trained medical students act as supervisors and moderaters and initiate the conversations with questions.

The station plan has been in place since November 2015. Since then, it has been continuously discussed and optimized by our advisory board as well as the group leaders. At our team’s discussion panel in October, the station setup was newly revised, following intensive literature review, and implemented nationally. The station plan was translated into English for our international teams and there was the opportunity for an international evaluation, in addition to the national evaluation by our advisory board.

Brief descriptions of the stations:

1) Different Tobacco Products and Extraction of Tobacco Smoke

This station is set up by a window or outside. During the first 10 mintues, common tobacco products are presented and discussed with the students: e-cigarettes, cigars, and regular cigarettes. How do these products differ from one another? How are they made? Over the next 10 mintues, the students work together to set up an experiment with a 1.5 L plastic bottle that has a hole at the bottom. The hole is sealed using a finger and the bottle is filled with water. A hankerchief is then placed between the cap and the neck of the bottle—the cap has a small hole in it as well. A cigarette is placed into this hole and lit. Then, the student removes their finger, causing the water to flow out and, as a result of the negative pressure, the entire cigarette to burn. Afterwards, the cap is removed and the hankerchief has a visible brown stain: The students were able to witness firsthand the tar and other harmful substances in cigarette smoke, which would otherwise end up in the lungs. This station provides a visual foundation for a basic understanding of the many advantages they have at their age by avoiding the pollutants, which have just been made visible.

2) Facial Attractiveness

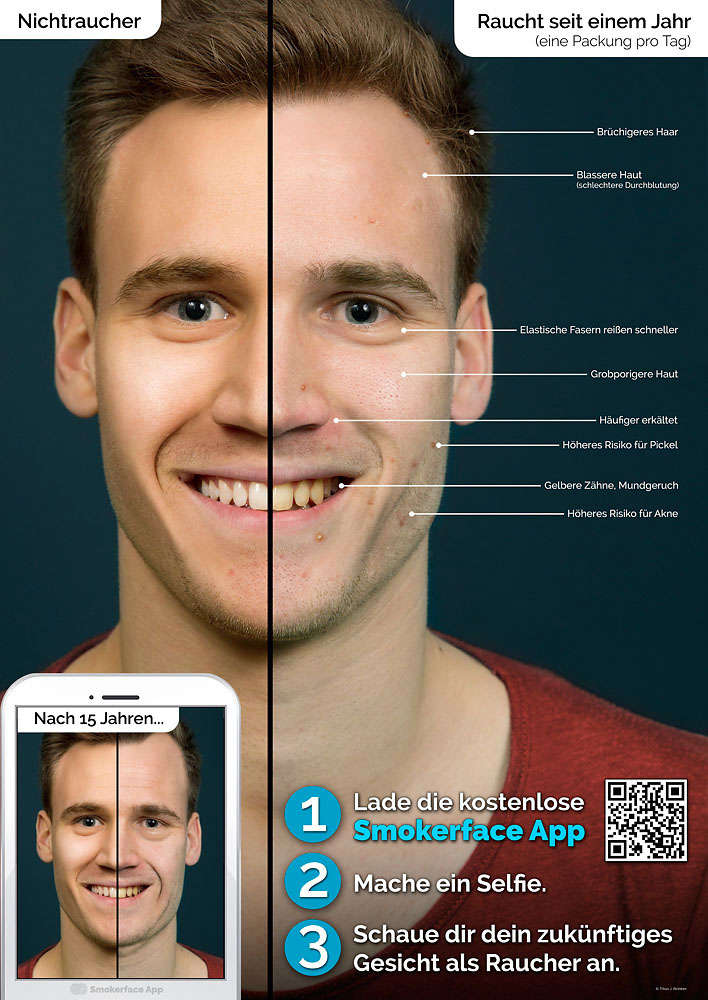

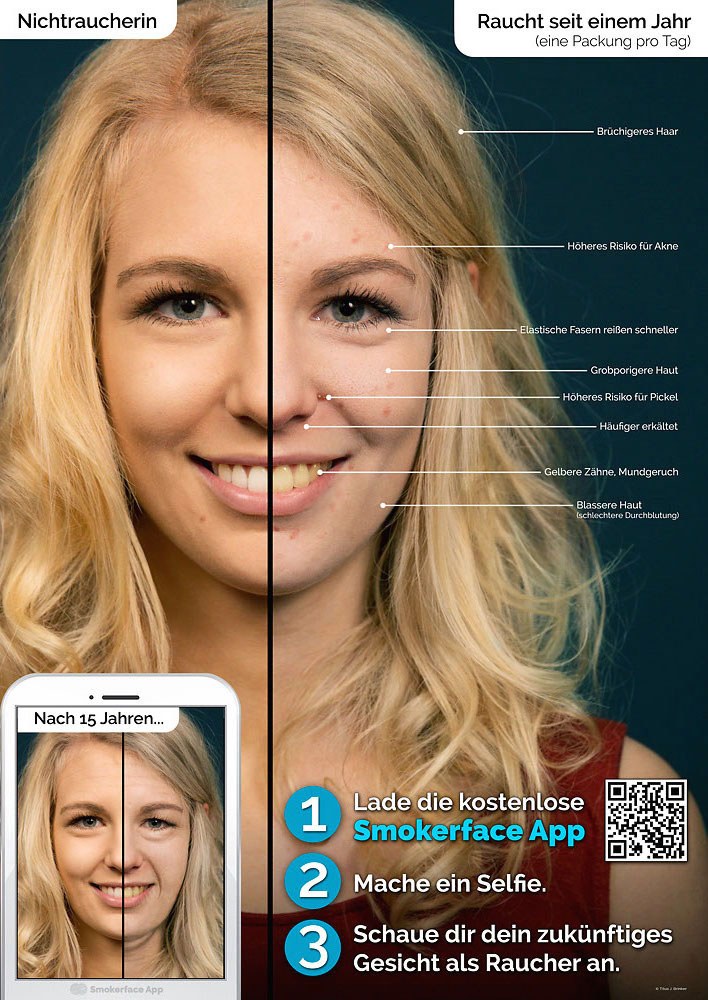

In the first part of this station, photos of identical twins, from the publication by Okada et al., are compared (one twin smokes, the other does not) [3]. Students discuss which differences stand out to them and who they think is the smoker. Students will also learn why and how smoking damages the skin and leads to breakouts [4].

In the second part, the Smokerface app is used with Galaxy Tab A Tablets (most often, students choose to work in groups with their best friends) within the smaller peer group, in order to reproduce the presented changes to their own face [1,5]. Because self-percieved attractiveness is the most important factor in self-confidence for kids this age [6], and to ensure that each student recieves age-based intervention, despite the successful pilot test, this part will be repeated on a smaller scale between closer groups (of friends).

3) Age-relevant, physical advantages of a smoke-free lifestyle and understading basic mechanisms

Pathomechanisms: Constricted vessels, elevated blood pressure, decreased tissue supply

Methods/Materials: Blackboard sketches, growth curves, model of a healthy body, three-way stopcock with disposable syringes (smaller tube = more force required to pump water through the syringe = elevated blood pressure in smokers and poor tissue supply!)

Age-relevant effects: loss of connective tissue in womens’ breasts = less volume/firmness; erecticle problems/impotence; growth disturbances in men during adolescense (non-smokers become taller! -> growth curve) [7], less cellulite in non-smoking women [8] and weight gain leading to obesity in females who do smoke (sketches!) [7,9], better lung growth in non-smokers and thus better performance capabilities (soccer players) [10].

4) The four phases of addiction and personal experiences: How can I stay away from cigarettes?

The goal of this station is to help the students understand the four stages of addiction in a fun way with our addiction memory game. The goal is to match 16 pictures including statements with four stages (Interest, Experimenting, Habituation, Dependence). Students should then assign themselves to one stage of addiction. Students are then asked whether they enjoy being in this stage of addiction. The answer is always the same: they don’t want to progress any further and become addicted. With this group opinion (peer pressure), there is a discussion about how one can prevent this progression. At this point, the students’ are asked to share their opinions and give each other tips—by doing this, students raise their own sense of self-efficacy [11] and, at the same time, create positive peer pressure [12].

The station is concluded by asking students if they know someone whom they would like to help quit smoking. Info cards for our no-cost, ad-free app, SmokerStop, are given to students to pass out around their local community.

Image 1: Info card recommending the Smokerstop app.

At the end of the workshop, the students’ finals thoughts are gathered to positively influence the students’ subjective norm and further increase the positive peer pressure; key aspects, such as less cellulite [8], taller height in men, and physical performance (including better erections [13]) are reinforced [12]. The workshop concludes with something very fun for the 7th graders: students perform cardio exercises in the classroom and then breathe through straws to simulate the decrease in athletic performace; in the Education Against Tobacco curriculum from 2013, over 90% of students rated this as the part that they enjoyed the most and is therefore perfectly suitable for 7th graders. The medical students hang the first two posters of the Smokerface Poster campaign in the classroom to enhance the future effects of smoking and then say goodbye.

Image 2: Poster of the Smokerface campaign, which is hanged up in the classroom at the end of the visit.

Want to learn more? Read our publications!

References

- Brinker TJ, Seeger W, Buslaff F: Photoaging Mobile Apps in School-Based Tobacco Prevention: The Mirroring Approach. J Med Internet Res 2016, 18(6):e183.

- Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R: School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013, 4:CD001293.

- Okada HC, Alleyne B, Varghai K, Kinder K, Guyuron B: Facial changes caused by smoking: a comparison between smoking and nonsmoking identical twins. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2013, 132(5):1085-1092.

- Schafer T, Nienhaus A, Vieluf D, Berger J, Ring J: Epidemiology of acne in the general population: the risk of smoking. The British journal of dermatology 2001, 145(1):100-104.

- Brinker TJ, Seeger W: Photoaging Mobile Apps: A Novel Opportunity for Smoking Cessation? Journal of medical Internet research 2015, 17(7):e186.

- Harter S: Causes and Consequences of Low Self-Esteem in Children and Adolescents. In: Self-Esteem: The Puzzle of Low Self-Regard. edn. Edited by Baumeister RF. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1993: 87-116.

- O’Loughlin J, Karp I, Henderson M, Gray-Donald K: Does Cigarette Use Influence Adiposity or Height in Adolescence? Annals of Epidemiology, 18(5):395-402.

- Stavroulaki A, Pramantiotis G: Cellulite, smoking and angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) gene insertion/deletion polymorphism. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2011, 25(9):1116-1117.

- Gasperin LdOF, Neuberger M, Tichy A, Moshammer H: Cross-sectional association between cigarette smoking and abdominal obesity among Austrian bank employees. BMJ open 2014, 4(7):e004899.

- Gibbs K, Collaco JM, McGrath-Morrow SA: Impact of tobacco smoke and nicotine exposure on lung development. CHEST Journal 2016, 149(2):552-561.

- McEachan RC, M; Taylor, NJ; Lawton, RJ;: Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review 2011, 5:97–144.

- Ajzen I: Theory of planned behavior. Handb Theor Soc Psychol Vol One 2011, 1:438.

- Gades NM, Nehra A, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ: Association between smoking and erectile dysfunction: a population-based study. American journal of epidemiology 2005, 161(4):346-351.